The odd one out: visual arts within festival culture

The odd one out: visual arts within festival culture

Laetitia Wilson

Once a year when summer hots up in this far-flung city of Perth, things come alive, people step out into the streets and the face of the city is transformed into a vibrant and culturally stimulating place to be. This occurs when Fringe World launches in January and then dovetails with the Perth International Arts Festival in February. Both festivals are strong in the performative arts and here, I will consider how the lesser represented visual arts have been placed within them over the last few years and what the vision for the future holds.

The Perth International Arts Festival is the longest running annual, international multi-arts festival in this part of the globe. Since its inception in 1953, it has promised arts of the highest international caliber and as with most arts festivals on the planet, performing arts is its raison d’être. Given this, the visual arts will never be dealt the same level of promotion or depth of continuity. However, this is not to say that it is brushed aside. In 2008 the PIAF team, under the Directorship of Shelagh Magadza, acknowledged the need for closer attention to the visual arts and appointed established curator and independent arts consultant Margaret Moore as visual arts program manager. Through Moore’s vision, visual arts acquired a new prominence. Driven to elevate the genre, Moore initiated a dedicated publication, distinct from the festival guide, focused entirely on the visual arts. Since 2009 this document has come into its own as a stimulating festival publication, communicating information and promoting the exhibitions. Curatorial essays now offer a probing point of entry into what might otherwise seem like a disparate assortment of art shows.

PIAF has maintained a keen interest in art in the public realm, following its original charter written by Professor Fred Alexander in 1953, who stated,

“Don’t allow the Festival to become the exclusive preserve of the ultra-highbrows who might be tempted to forget that it is primarily a festival for the people of Perth.”

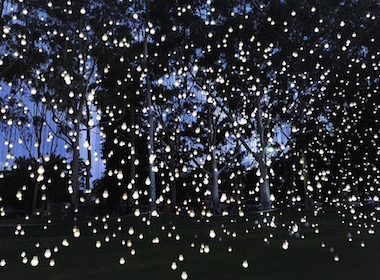

Given hefty ticket prices commanded by many of the music and performing arts shows, the visual arts at least proves an adherence to this vision, with both its free exhibitions and large-scale public, outdoor spectacles. Consider Jeppe Hein’s Appearance Rooms - the fountain displayed outside PICA and subsequently purchased by the City of Perth; or Jeremy Deller’s Sacrilege, the giant bouncy castle version of Stonehenge; or Jim Campbell’s captivating Scattered Light, with its play on viewer’s perceptions, inviting different interpretations relative to distance or proximity. These kinds of projects are large-scale, experientially rich and accessible works. They are art for the people beyond the walls of a gallery.

For Moore this is about providing the widest possible access to art of the highest standard, it’s about optimising outdoor space to install art of expansive scale and enabling the possibility for participation, as well as providing, “…opportunities for increased public access to contemporary art experiences beyond museum walls.” This year the Giants created by Royale Deluxe appeared to leave the people of Perth awestruck. As the festival highlight, the girl and the deep-sea diver navigated the streets with their quasi ANZAC-themed narrative and proved a major public hit.

More closely aligned with the visual arts, the Subiaco pARk project provided an extreme contrast to the noise, scale, intensity and high visibility of the Giants. It was also one of the few shows with a strong local focus, featuring the work of eight local artists. The pieces were created in association with architecture and design studio, Felix, who were the technical expertise behind the augmented reality realisation. The works were only visible through the interface of devices such as tablets or smart phones and despite this technological mode of engagement the exhibition did get people outdoors and interacting within the environment of Subiaco’s Theatre Gardens. It also provided a compelling commentary on the role and archetype of the sculpture park as a permanent fixture populated with often large and grandiose artworks. The augmented reality works expanded this model into the virtual and also inverted it to result in small and medium-scale, immaterial and fickle works, created in response to the site.

In the past seven years Moore has focused on partnering with organisations, independent curators and artists to build cooperative relationships that can realise a shared vision underpinned by a strong curatorial ethos, that builds a synonymous sense of ownership. Moore has a personal predilection for contemporary art but is open to conversation with local curators, artists and galleries to help bring about their vision in cohesion with the festival program. Moore also describes the need to “…bring some resonance or linkage across the program” so that there is context for people going from one project to another.

In the past seven years Moore has focused on partnering with organisations, independent curators and artists to build cooperative relationships that can realise a shared vision underpinned by a strong curatorial ethos, that builds a synonymous sense of ownership. Moore has a personal predilection for contemporary art but is open to conversation with local curators, artists and galleries to help bring about their vision in cohesion with the festival program. Moore also describes the need to “…bring some resonance or linkage across the program” so that there is context for people going from one project to another.

This was most fully realised in the 2013 festival with its emphasis on the medium of light. The idea of a theme can be too restrictive or defined but this focus on medium enabled a more fluid association between shows. Jim Campbell exhibited both at Kings Park and at the Lawrence Wilson Art Gallery in the group show Luminous Flux, UWA hosted its major Luminous Nights event, Grazia Toderi’s projections all about light graced John Curtin Gallery and Ross Manning’s installations glowed at PICA. Since this year of illumination, there has been less explicit links evident in the festival program.

2014 saw the connection between PICA and AGWA through the presentation of the spectacular work of William Kentridge and this year, foreshadowing the centenary of ANZAC, we saw points of connection drawn across the program from the Giants, to the Black Diggers theatre show, to the Theatres exhibition at the WA Museum and Moana Project Space.

The works in Theatres were based on artists responding to zones of conflict and half of the show was presented at cinematic scale, which created links with the projection-based exhibitions at both Fremantle Arts Centre and John Curtin Gallery. The alignment of these venues put the cohesive vision of Moore into practice by extending the work of the artist Ragnar Kjartansson across both. This was arguably the highlight of the visual arts program because it enabled a full experience of a single artist’s practice. The experience was less like an exhibition as a packaged product and more like an evolving and intimate journey into an artist’s psyche.

The works in Theatres were based on artists responding to zones of conflict and half of the show was presented at cinematic scale, which created links with the projection-based exhibitions at both Fremantle Arts Centre and John Curtin Gallery. The alignment of these venues put the cohesive vision of Moore into practice by extending the work of the artist Ragnar Kjartansson across both. This was arguably the highlight of the visual arts program because it enabled a full experience of a single artist’s practice. The experience was less like an exhibition as a packaged product and more like an evolving and intimate journey into an artist’s psyche.

PIAF aims to bring international art to Perth audiences. Core to this in 2015 was AGWA’s exhibition of the pearlescent reverie of Japanese artist Mariko Mori. Titled Rebirth, this exhibition delved into the spiritual and celestial with a suite of works of variable quality whose materiality sadly highlighted the tired appearance of our state gallery. There is often a bemoaning that such a focus on the international, or national (Tracey Moffat at PICA and Yirrkala at the Lawrence Wilson Art Gallery), comes at the expense of the support of local practitioners. This is one of the challenges navigated by Moore.

If the budget devoted to the Giants was invested locally, the returns over time could arguably make for a rich and sustainable change to the cultural face of the city.

Nevertheless, within the constraints Moore does seek to maintain and develop strong links at the local level. At the Western Australian Museum the second iteration of the Spaced project by IAS (International Art Space) was a global melting pot of socially responsive art from local, national and international practitioners. Then in addition to the Subiaco pARk project, there was An Internal Difficulty at PICA curated by Andrew Nicholls and presenting the results of a group residency by Perth based artists in the Freud Museum in London. This curious exhibition invited the viewer to follow a path, never knowing what was hiding around the next corner – like the workings of the unconscious mind. The end of this winding journey was met by an image of pathos by Thea Constantino – a wax figure of Freud, castrated.

In 2015 PIAF director Jonathon Holloway has passed the baton onto Wendy Martin. Martin has a background in the performing arts but throughout her various roles she has displayed interest in supporting the visual arts. She speaks of an holistic vision for the festival, where the arts are not necessarily distinct, but integrated across disciplines; where there is cross pollination across all the artforms and audiences follow “…narratives that thread the performing arts to the visual arts and music, so that across the festival there’s a story.” This mirrors broader trends in contemporary art where the barriers between artforms are broken down. Martin also reiterates Moore’s emphasis, that, “It is important that generally for a festival there are things that people stumble across, so that work is not just for the initiated, so that people might encounter beautiful or mad things as they wander through the city.” Through Martin we can expect the public realm to continue under the spotlight, revealed through this more integrated approach across the arts.

In 2015 PIAF director Jonathon Holloway has passed the baton onto Wendy Martin. Martin has a background in the performing arts but throughout her various roles she has displayed interest in supporting the visual arts. She speaks of an holistic vision for the festival, where the arts are not necessarily distinct, but integrated across disciplines; where there is cross pollination across all the artforms and audiences follow “…narratives that thread the performing arts to the visual arts and music, so that across the festival there’s a story.” This mirrors broader trends in contemporary art where the barriers between artforms are broken down. Martin also reiterates Moore’s emphasis, that, “It is important that generally for a festival there are things that people stumble across, so that work is not just for the initiated, so that people might encounter beautiful or mad things as they wander through the city.” Through Martin we can expect the public realm to continue under the spotlight, revealed through this more integrated approach across the arts.

Fringe World

Over the past few years the Fringe festival, called Fringe World since 2011, has become less of a fringe dweller and more of a fierce commercial entity. With its re-defined and growing brand, booming sales, expanding use of space and amassing fans, it has been taking Perth by storm. Billboards advertise 31 days of Perthect and the magazine style program just keeps getting fatter. It has become less about appealing to the alternative crowd, as in the earlier Artrage days, and more about pleasing (and teasing) the people of Perth, with a significant emphasis on Burlesque performance. This has happened under the directorship of Marcus Canning from 2002, who re-branded Fringe to Fringe World, handing over the Directorial reins to Amber Hasler in 2014. Working across cultural, social and economic terrains, Hasler is primarily focused on the growth of Fringe World as a festival with broad market appeal.

Fringe World still suffers from myopia toward the visual arts. Since 2013 the visual arts have been reduced to a mere two pages in the program, as an assortment of tangentially related exhibitions and events, drowned out by the peripheral noise of performance. Like PIAF, the visual arts would benefit from dedicated time, resources and individuals being devoted to raising its profile. Hasler notes that its current diminished standing in Fringe World is in part structural, given the festival’s reliance on artist-initiated content. She makes the point that unlike the many performance-based shows that pass through a given venue, visual arts shows generally require dedicated space for a longer duration, they are often fixed entities and they fall short in the area of economic gain that underpins the Fringe model.

What Fringe World does do successfully in terms of the visual arts is provide a platform for the support of local experimental practices, emerging artists and artist run initiatives.

Places like Paper Mountain, Free Range gallery, PS Art Space, Spectrum Project Space, various bars, cafes and the city streets all occupy the program. Even AGWA comes to the party with exhibitions such as Picturing New York in 2013, and New Passports, New Photography in 2015 with the gallery opening hours extended for Fringe audiences. Hasler claims visual arts to be an important part of the program, with ample opportunity for more individuals and organisations to step up.

Although the artists and exhibitions included within the program are not curated by Fringe and not necessarily linked to the festival’s ethos, Hasler remarks that over the years the art practices and exhibitions included have tended toward greater reflection of its general thematics. For example, the now closed Melody Smith Gallery featured prominently in the 2014 program with several shows relevant to Fringe, such as Eat Me – where the audience was invited to cut away at the artist’s, Rizzy’s, edible gown. Similarly this year’s winner of the Visual Art Award for best show was an exhibition called Mate at Paper Mountain that explored the kitsch of historical Australiana and resonated with the humour and girly glitz of Fringe World. For example, David Attwood’s iced VoVo biscuit nibbled into the shape of Kevin Rudd’s head and a photograph featuring a line of female lifeguards, against an ocean backdrop with swimsuits gleaming gold by Tarryn Gill and Pilar Mata Dupont.

As with PIAF, in Fringe World the visual arts benefit from high visibility in the public realm.

For 2015 it was hard to miss the large pink Brookfield Bunnies of Stormie Mills, which appeared at various locations. There was also the Cinematic Portraits of Chris Lawrence, sketched in real-time on the cultural centre screen. Beyond the dedicated delineation of visual arts as a category, it is apparent to all that creative dynamism in the public realm is irrefutably activated during Fringe World with the numerous wandering performers, random installations and hands on activities, such as the Make-a-Kewpie store by local artist Paula Hart.

For 2015 it was hard to miss the large pink Brookfield Bunnies of Stormie Mills, which appeared at various locations. There was also the Cinematic Portraits of Chris Lawrence, sketched in real-time on the cultural centre screen. Beyond the dedicated delineation of visual arts as a category, it is apparent to all that creative dynamism in the public realm is irrefutably activated during Fringe World with the numerous wandering performers, random installations and hands on activities, such as the Make-a-Kewpie store by local artist Paula Hart.

Within the global rise of festival culture both PIAF and Fringe World briefly elevate Perth to a pumping hub of activity. Festivals and their visual art exhibitions might be judged on their ability to produce memorable experience. In PIAF art works that have a memorable impact over the last few years have tended to rely on experiential depth rather than provocation, whereas the inverse could be said for Fringe World. If the future for PIAF promises cross-genre pollination and for Fringe World exponential growth, one place they do meet is in the public realm. Fortunately, it is the one unavoidable space, for anyone and everyone who steps out.

Laetitia Wilson completed a doctorate in 2011 in Art History at the University of Western Australia. For over half a decade she has lectured at UWA and currently works as Adjunct lecturer and Curator at the Lawrence Wilson Art Gallery, in addition to being art critic for the West Australian newspaper and freelance writer.

Rebirth, Mariko Mori, runs at the Art Gallery of Western Australia from 8 Februry to 29 June 2015.

Image Credits

-

Mariko Mori, 'Transcircle 1.1', 2004 (detail). Stones, Corian, LED, Real Time control system 336 cm in diameter: each sculpture: 110 x 56 x 34 cm. The Mori Art Collection, Tokyo. Photo: Richard Learoyd.

-

Jim Campbell, 'Scattered Light', 2010. Video Installation: custom electronics, LEDs, light bulbs, wire, steel; 80’L x 20’H x 16’D. Photo: Toni Wilkinson.

-

Ragnar Kjartansson, 'The Visitors', 2012. Nine-channel HD video projection, 64 mins. Photo: Elisabet Davids.

-

Ragnar Kjartansson, as above.

-

Chris Lawrence, 'Cinema Portraits', 2014. FRINGE WORLD Festival. fringeworld.com.au. Photo: chrislawrenceart.com.