Review: Directors’ Cut at John Curtin Gallery

Review: Directors’ Cut at John Curtin Gallery

words by Perdita Phillips

Exhibition: 18 May to 8 July 2018

Tucked away at my writing desk is a cassette tape of an interview that a young, white middle-class art student did with Nyoongar Artist Tjyllyungoo, Lance Chadd, in 1989. The circumstances behind my first-year assignment was a presentation that the then Curtin University lecturer, Ted Snell, gave at the School of Art on the Carrolup artists as part of a unit on Western Australian art. In subsequent years, many more West Australians have rediscovered the history of the Carrolup School and its impact has been reassessed in the light of the subsequent currents of postcolonialism, reconciliation and decolonisation, from the 1980s to the present.

A selection of fragile pastels and watercolours from the Herbert Mayer Collection of Carrolup Artworks form a strong focus point in Directors’ Cut on show at the John Curtin Gallery. Conceived as a celebration of fifty years of the Curtin University Art Collection and the twenty-year anniversary of the gallery, current JCG director Chris Malcolm invited the two previous directors (John Barrett-Lennard 1995-2001 and Ted Snell 2001-2008) to look at the collection afresh.

All three curators have worked with the noticeable constraints of a university collection — that of it needing to fulfil a number of criteria that impel it in different directions — to this day. In a bountiful show, one hundred and twelve of the estimated 3005 objects in the collection, are on display.

All three curators have worked with the noticeable constraints of a university collection — that of it needing to fulfil a number of criteria that impel it in different directions — to this day. In a bountiful show, one hundred and twelve of the estimated 3005 objects in the collection, are on display.

John Barrett-Lennard has delved deep into the collection’s initial days to pull out works that strike one as representative of modern and post-modern art trends. These earlier, mostly two-dimensional works, feel quite self-contained. Of note is a salon hang that includes a set of international prints which one suspects had a strong didactic purpose — of bringing actual and affordable examples of influential artists — to the fledgling WAIT art school in the early 1970s. But tucked in here also are notable Western Australian practitioners such as Miriam Stannage. Two early photographic prints of Allan Vizents[i], The perfect sleeper (1980) and Letter to Guildford (1980) have also been included. Both follow the same format: a street image in one half the picture plane and an area of sparse symbols and alphanumeric fragments in the another. The former work shows a faded advertisement for a mattress and the latter shows a stick-man letterbox decoration seemingly about to bound jauntily down the road. And whilst we are now today very familiar with Instagrammers capturing urban psychogeographic moments, Vizents’ work reminds us of when the postmodern moment reached the Western Australia art scene in that same decade. These two photographic compositions represent the beginnings of Vizents’ critical investigation into interactions between text and image and the processes of reading and decoding. More than just the peculiar subject matter, it is the enigmatic exchange between the representational and symbolic content, that makes us look again.

I was also quite surprised when returning to a work by Carol Rudyard[ii] chosen by Chris Malcolm, who has selected out artworks that are for various reasons unsuitable for permanent display in office spaces. Apocryphal tales (1994) is a video projection inside an austere but gilt frame, with a sound track by Ross Bolleter. It comments in part on the gallery as cultural validator and the pervasiveness of the media, but unlike the artist’s earlier video installations, a cool domestic aesthetic is not featured here. Rather, there are three distinct episodes that jostle against each other in absurd ways: the art historically-heavy references to Judith and Holofernes are juxtaposed against the adventures of Wunderhund at Uluru. This made me laugh. The tone of the third apocryphal tale (Guys and Dolls) is darker as it montages together fragments of dolls, putti, blood and guns. Like the work of Vizents, there is a push and pull between symbolic and representational content, but in the intervening years something has lessened the serious (unfunny) grip of theory that might have typified postmodernism in Perth at that time. The standard definition screen proportions and raw, lo-fi superimpositions of different footage, have gone from fresh to dated, to fresh again. One views it not quite sentimentally, nor nostalgically, but with good-humour. The montage and juxtaposition that Rudyard used have not lost their sharpness, but they appear now not to be in the service of postmodern parody or irony, but working towards a much more eternal mischief.

Like many art schools, Curtin University has collected the work of students from graduation shows. Given the high rate at which art graduates move into different fields post-degree, it is always an intelligent wager as to who will be a marker of innovation and influence in the long-run.

Ted Snell has chosen to display work of graduates who have made an impact locally, nationally and internationally. Jewellery by Sarah Elson, Carlier Makigawa and Helen Britton is on display, as well as works by Nalda Searles, painter Tom Alberts, Holly Story and Laurel Nannup.

Ted Snell has chosen to display work of graduates who have made an impact locally, nationally and internationally. Jewellery by Sarah Elson, Carlier Makigawa and Helen Britton is on display, as well as works by Nalda Searles, painter Tom Alberts, Holly Story and Laurel Nannup.

In a similar way to Vizents and Rudyard, George Egerton-Warburton also harnesses elements of the absurd. His oil on canvas Meth lab (2009) from his Honours year[iii] presents an interior view of a cluttered kitchen rendered in dissolute blocks of colour daubs and spraycan paint. Based on a found online rent listing, Egerton-Warburton regards the painting as an ‘extraction from a series of coincidences and tangents’[iv]. Today the artist continues to weave together disparate ideas into suites of associations in each of his exhibitions. Like many contemporary artists, instead of producing discrete, autonomous works, intentions are fractured into the multiple, contingent forms that appear scattered in the gallery. This suits Egerton-Warburton’s interest in probing the structures and topologies of the everyday and the way that unrelated facts and experiences can come together.

That university collections are limited by the practicalities of budgets, finite storage space and of where artworks can be shown in the public corridors and office spaces of the institution, is common sense. Installations, time-based media and performance works are difficult to collect, even in documentary form. But collections are also up against the changing nature of the relational boundaries of an artwork, typified by Egerton-Warburton’s approach.

In the case of Julie Gough’s two-screen high definition video Larngerner (The colour of country) (2018, courtesy of the artist), one could interpret the slow, still long-shots of agricultural and intact ‘natural’ landscapes as calming and reassuring, especially given the pervasive trope of Tasmanian landscape-as-wilderness[v]. But, within this slow-cut editing is footage of shell middens and anomalous back lane bonfires, one is drawn back into reassessing what one is watching. What is ostensibly on display is not the full story and the scenery is not apolitical. The artist then adds in overlays of voices and images of material from the archive that builds a web of relations extending out from the filmed landscape, to include the critical and political consequences of the historic erasures of Tasmanian Aboriginal culture. What appears peaceful, hides other histories and other ethical demands. This extension of the artwork to include its wider conceptual terrain, makes contemporary art a vital if difficult ‘agent’ for audiences to fully encounter (read the didactic panels and then harness your ability to make connections outside of the artwork) — and for collections to collect, and to fully do justice to. This is an ongoing challenge that contemporary art collections face.

Lance Chadd’s uncles Reynold Hart and Alan Kelly, were among the Carrolup child artists[vi]. The full story of the Carrolup school and the return of the Herbert Mayer Collection of Carrolup Artworks is detailed elsewhere[vii]. What is most relevant here is the responsibility entrusted to John Curtin Gallery to support the access to and sharing of, the Carrolup Collection. This has occurred firstly through the Koolark Koort Koorliny (Heart Coming Home) exhibition and oral history program and also through the touring of selected works back to the Southwest. These programs have been enormously significant to the descendants of the child artists[viii]. The Carrolup Elders Reference Group gave permission to JCG to tell the story through a virtual field trip[ix] which has ‘activated’ the collected works for students world-wide through behind-the-scenes live Skype tours and supporting educational materials.

Through the combination of these programs, new and renewed relationships have spiralled outwards from the artworks, going a long way to fulfilling the Carrolup Project mission to ‘promote healing within our broader communities and achieve enduring reconciliation’[x].

Despite its overall size, Directors’ Cut represents a small fraction from the overall collection. Some artworks have rarely been seen by the public and others are a window into the historical development of Australian art since 1968. With the inclusion of a number of recommendations for future purchase put forward by Chris Malcolm and John Barrett-Lennard, Directors’ Cut also provides an argument for the collection’s continuing relevance to the University community, its visitors, and present and future custodians.

Dr Perdita Phillips is an Australian artist, researcher and writer whose practice revolves around environmental issues and social change. She has a wide-ranging and experimental conceptual practice that traverses and integrates art, science, walking, listening, human communities and nonhuman worlds. In 2017, she was Artsource’s Online Magazine Editor, commissioning and editing industry articles, features and artist reflections. www.perditaphillips.com www.lethologicapress.org

Images (top to bottom)

-

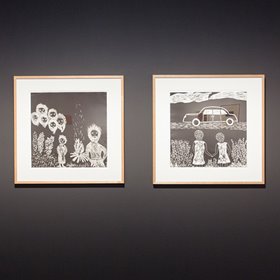

Laurel Nannup, (left) As grandad was speaking out of the darkness came about six men…, 2001. Woodcut on BFK paper, 57.5 x 57.5 cm. (right) …crying our eyes out, 2001. Woodcut on BFK paper, 57.5 x 57.5 cm. Image courtesy of John Curtin Gallery.

-

Directors’ Cut (installation view), John Curtin Gallery, 2018. Image courtesy of John Curtin Gallery.

-

Directors’ Cut (installation view), John Curtin Gallery, 2018. Image courtesy of John Curtin Gallery.

-

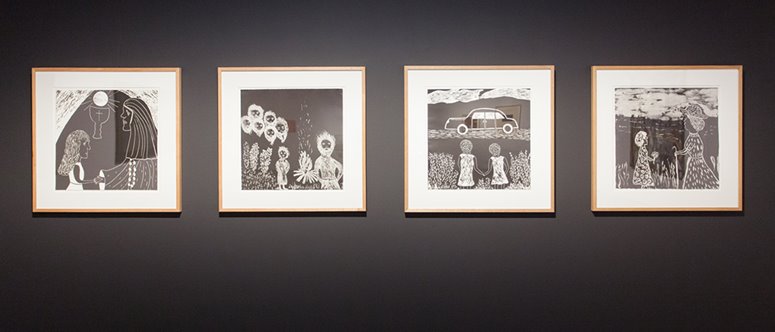

Laurel Nannup, (left to right) I felt like an angel that day, 2001. Woodcut on BFK paper, 57.5 x 57.5 cm; As grandad was speaking out of the darkness came about six men…, 2001. Woodcut on BFK paper, 57.5 x 57.5 cm; …crying our eyes out, 2001. Woodcut on BFK paper, 57.5 x 57.5 cm. …in the end I got my dress with the pretty red roses…, 2001. Woodcut on BFK paper, 57.5 x 57.5 cm. Image courtesy of John Curtin Gallery

[i] American/Australian artist who arrived in Perth in 1978 and died in Sydney in 1987. Whilst in Perth he edited Praxis M and was involved in Media Space, an artist collective that explored the new media and digital technologies.

[ii] Rudyard was part of the inaugural 1967 student intake in the art department where she concentrated on hard edged colour painting. She later taught Art History at Curtin University. It wasn’t until the 1980s that she began experimenting first with slides and later with video installations.

[iii] His peers will remember George Egerton-Warburton’s graduate work of the previous year (Road Trains Will Never Tear Us Apart) which involved cycling from Perth to his home near Kojonup collecting roadkill in a makeshift cart.

[iv] Email communication with gallery staff, with the author’s italics.

[v] ‘Attenborough narrates the story of a vast island wilderness - ancient forests, pristine rivers & spectacular coastline. Seasons vary from dry heat, strong winds & cold bringing wombats, wallabies & platypus out in daylight’ Australian Broadcasting Corporation, ‘David Attenborough's Tasmania’, 2018, 3 Jun 2018, https://iview.abc.net.au/programs/david-attenboroughs-tasmania/ZW1100A001S00

[vi] Fisher, L, ‘Lance Chadd b. 1954’, 2011, 25 October 2012, https://www.daao.org.au/bio/lance-chadd/biography/

[vii] e.g. Forrest, S., & Johnston, M, ‘Koolark koort koorliny: Reconciliation, art and storytelling in an Australian Aboriginal community’, Australian Aboriginal Studies, 1, 2017, 14-27, https://search-informit-com-au.dbgw.lis.curtin.edu.au/documentSummary;dn=906846521925271;res=IELAPA

Haebich, A, ‘Picture Gallery: The return of the Carrolup drawings’, Griffith Review, Edition 47: Looking West, 2015, 3 Jun 2018, https://griffithreview.com/articles/the-return-of-the-carrolup-drawings/

Haebich, A, ‘The Return of the Carrolup drawings’, Griffith Review, 47: Looking West, 2015, 3 Jun 2018, 97-104.

Pushman, T., & Smith Walley, R, ‘Koorah coolingah = Children long ago’, Occasional paper (Berndt Museum of Anthropology), 8, 2006.

Sokil, N, ‘Show us a light: the art of Carrolup’ [DVD], Contemporary Arts Media, South Melbourne, 2005.

Stanton, J. E. ‘Nyungar landscapes: Aboriginal artists of the South-West, the heritage of Carrolup, Western Australia’, Occasional paper (Berndt Museum of Anthropology), 3, 1992.

[viii] see Curtin University School of Media Culture and Creative Arts, Haebich, A., Johnston, M., Woods, I., South West Aboriginal Land and Sea Council, Hoelker, D., Morich, C. and Kuhlenbeck, B., ‘Koolark Korl Kadjan (Spiritual Return Home)’, 2016, 3 Jun 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Of5NWzazpao

[ix]3 Johnston, J, ‘Explore JCG: The Herbert Mayer Collection of Carrolup Artwork’, 2017, 3 June 2018, https://education.microsoft.com/jcg

[x] Personal communication with Jess Johnston, Carrolup Project Assistant at Curtin University.