What do Perth artists have to say?

What do Perth artists have to say?

Commentary by David Bromfield

December 2013

"We have nothing to say and we are saying it!"1

"Create. Curate. Collaborate."2

Cage’s aphorism points to a familiar paradox. On one hand a successful work should ‘say’ everything there is to say, on the other, the work of an artist with nothing to say may well say nothing of any value.

In Perth now, many artists believe discussion or dialogue is futile. It will not help them make better art or further their career. They have concluded there is nothing to say and decided to say nothing. Maybe no one wants to listen. There is a pervasive sense of dullness, silence, of absence of things, which are not, and perhaps should be present, in the day-to-day business of making and enjoying art. Art biz small talk is still okay but that’s about it. Many are embarrassed by any sign of critical engagement, or social commitment.

Simultaneously, there has never been more demand, more opportunity in Perth for artists to make a noise, to speak out about their art, advocate for it, in the community of artists, the art audience and the infrastructure of public galleries, art institutions, the art market, collectors and art fashions which together might be called the ‘Art Apparatus’.3

Like ‘The Author’, ‘The Artist’ as a concept has been dead for a long time, but is still greatly missed, particularly by art administrators, curators, critics, professors, patrons and the like, for its unique ability to authenticate and assist their various hierarchical functions. The Art Apparatus can no longer recognise what I believe remains the central role of art as a force for freedom, generosity and the chance to make a difference, in every possible sense. Yet, even though it thinks of art as a privileged form of showbiz it still needs the mythic ‘Artist’ to speak for it.

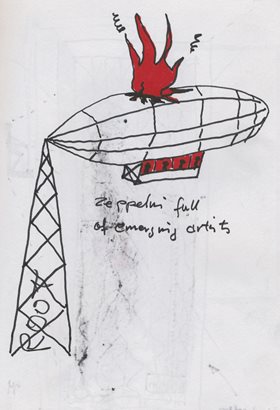

In the absence of ‘The Artist’, Voodoo sociologists at Curtin’s ‘Creative Workforce Team’ attempt to resurrect it as a zombie creative worker, to ‘Give the WA creative sector a voice!’ The search is on for articulate zombies who will say the right thing to ‘boost visibility, inform funding and skills development and build a more sustainable creative workforce.’ (!!) The AFL often wheels out a tongue-tied teenager for the cameras, struggling to remember the half dozen mindless football cliches his coach just taught him. Perhaps, this is what art needs in these ‘conservative’ times – a flexible ventriloquist’s dummy, stuffed with art cliches, aspiration and ambition, roughly resembling an emerging artist perhaps?4

In the 1990s PICA, under its foundation director Noel Sheridan, was a wide-open membership-based organisation with a staff of two or three people and a lot of energy for debate. Now, to pay its ever-growing bills it strives to attract the corporate dollar to a ‘Salon’ with an exclusive high-price opening. It also charges for conferences, thereby excluding many artists. Whether this change has been good, bad or just inevitable, it provides an index for similar, wider changes that may explain the reluctance of artists to participate.

By contrast, the slogan of ArtLab Media Pty Ltd urges the basic unity of creation, curation and collaboration as interdependent elements of any art practice. ArtLab may be rehabilitating the possibility of open unlimited creative discussion. It recently organised a large event at the Perth Conference Centre to discuss, not the business as usual issues of the Art Apparatus, but ‘creation and creatives’ in various forms and locations.

Once one lets go of the fetishised idea of ‘The Artist’ it becomes much easier to talk about art and creativity without embarrassment. ArtLab is unashamedly entrepreneurial but not corporate or market driven. A bucket for gold coin donations was at the door of their recent, pop up event in William Street. They told me they had returned $8,000 to artists during a previous event but needed money to buy a chopping board for their sausage sizzle. In ArtLab and many similar groups the importance of artists’ voices is taken for granted.

The proliferation of informal groups such as ArtLab testifies to an unmet need for dialogue and debate amongst artists. They may appear naive from the viewpoint of the art institutions, as may the contents of many pop up exhibitions themselves. Artists occasionally need naivety for their art. Early in his career Monet became notorious for showing a painting in a Paris shop window.

Recent discussions of art here are often marked by supremely dull ‘show and tell’ displays of careerist ambition.

Self-serving cynicism often paraded as an amusing, but knowing, irreverence, so as to cut off critical reflection, in favour of a belief that ‘nothing can make any difference’, so let’s talk about how to put the paint on, how to get the next grant, how bad the art schools are and how far you have to bend over to get a show at L and K.5

Perth’s artists are responsible for their present indifferent situation. Nonetheless, strangely divided as this is, it could be quickly changed if our art institutions open up to a broad-based no-holds-barred debate about what really matters about art and artists. It may also help to consider some of the causes that, over the years, have led to this situation. They range from a superficial reception of ‘theory’, the rise of corporatism in PICA, the Art Schools and other institutions intended to support the visual arts and artists, a banal local notion of Taste and the Art Market, the slow death of Art Criticism and what Maurice Breen calls, ‘The Internet’s Unintended Consequences.’ These and many other possibilities offer powerful reasons to abandon any attempt to ‘make a difference’ through art.

‘Saying nothing’ may be a survival strategy in a time of absolute indifference.

Superficial theory began its assault on local creativity and commonsense in the 1980s. Feminism repeatedly confused representation with reality, (e.g. arguing that a painting of sexual violence is identical with actual sexual violence). This Stalinist nonsense got a firm grip in our fine art schools and began to write the script as to what was permissible in art practice here, thereby abolishing one of the fundamental distinctions required for any art work. Local ‘postmodernists’ rejoiced in the end of critical master narratives and the death of the author, celebrated absolute relativism as a new freedom, but failed to notice that many artists, broadly identified as postmodern, (Rauschenberg, Beuys, Richter, Tracey Emin et al), were desperately engaged with strategies to reassert difference within their practice.

Provincial Perth amplified the bogus absolute relativity of postmodernism, to a dull degree zero of monolithic indifference. The Internet has extended this to the point where every idea and attitude has the same value.

PICA now struggles to produce exciting original exhibitions; the change from energetic open slather to a highly curated Kunsthalle has not done it much good. The problem with corporate gatekeepers and the corporate process is, in the immortal words of Dave Graney that they want to get there, but they don’t want to travel. Corporate patrons look only for guaranteed unproblematic ‘quality‘.

As Perth lost most of its significant galleries, it lost a generation of dealers who were also dedicated, generous advocates. They encouraged their artists to engage with the broader debate, partly because they understood that building an artistic practice and reputation, and the demand for their art both took any number of years. This approach has been replaced by an ‘art industry’ that generates product for an ‘art market’ highly conscious of its turnover and annual bottom line, that no longer understands that ‘it can only function through a disavowal of the economic.’6

Many of the artists who confront the results of these events were not born when they began, yet only their voices urging the absolute necessity of art and creativity have any hope of changing them for the better.

-

-

1 Adapted from John Cage.‘Silence’ various editions

-

2 Artlab

-

3 Perth provides a regular diet of public/private conferences, such as the event associated with In Confidence: Reorientations in Recent Art at PICA or the Artspoken series at Fremantle Arts Centre.

-

4 The emerging artist is, of course, another construction of the Art Apparatus. The Curtin Creative Workforce text is taken from a postcard issued to recruit responses to a questionnaire, which can be found at http://research.humanities.curtin.edu.au/projects/. However, those interested in the economic position of the artist in Australia would be better off reviewing the work of Professor David Throsby, such as ‘Don’t Give Up Your Day Job’ 2002.

-

5 This is not a comment on L and K. It is about the attitude and ambition of Perth artists.

-

6 The best essay on the unique features of the market for significant cultural goods remains Bourdieu’s ‘The Production of Belief: Contribution to an Economy of Symbolic Goods’ in Pierre Bourdieu “The Field of Cultural Production” Polity Press/Blackwell’s Cambridge 1993 pp 74-111

David Bromfield is Director of the Kurb Gallery in Northbridge, and recently Director of the Victoria Park Centre for the Arts. A long serving former critic for The West Australian, he will soon launch www.tincanvas.org a blog/review, in an attempt to remedy what he regards as the total absence of art criticism in Perth.

This article featured in the Artsource Newsletter, Summer 2013/14.