The Role of Art in Decolonisation

The Role of Art in Decolonisation

words by Cassie Lynch

PRESENT TENS(ION)E

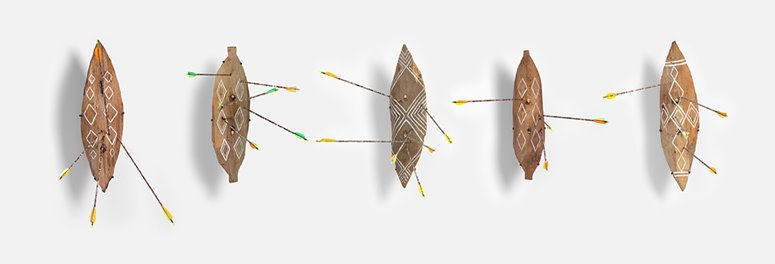

Steaphan Paton’s Cloaked Combat (pictured below) tells the tale of Indigenous resistance with compelling simplicity. Bark shields painted in traditional designs are filled with arrows with fluoro plastic fletching.

Though people are absent from the artwork, the line of bark shields suggest a row of warriors facing down an adversary. The shields are raised, the arrows have been fired and we, the viewers, find ourselves in the aftermath of the confrontation. Some viewers of the artwork will feel like they carry the shield, some will feel like they fired the arrows, and some viewers, like myself, will feel like both shield-carrier and arrow-shooter. The artwork suggests a clash between cultures, the ancient bark shields defending against modern arrow weaponry: timeless Indigenous sovereignty versus cutting-edge Western progress. There were no high-tech plastic arrows during colonial times, so one could infer that this particular stand-off is not a recreation of a confrontation of the past, but a very current conflict. The shields hover against the gallery wall, still and straight. Strong. Firm. How long have the shields been raised for? Does the artwork infer resistance or a stalemate?

The steadfastness of the shields speaks to me as a researcher in the field of postcolonial theory[i]. The shields aren’t smashed, they aren’t lying on the floor, they aren’t burnt or aged. This isn’t an artwork that refers to lives lost in the past in frontier conflict, this artwork infers a resistance to invasion that started two hundred years ago and continues today. The sculpture is the present tens(ion)e. The warriors are still here, their stance is strong.

PRESENT DAY

One of the main tenets of colonial ideology is that Indigenous culture is a less-evolved version of Western culture[ii], and that Indigenous culture was ‘progressing’ towards the Western model. This kind of thinking led to the initiation of assimilationist policies, as if it was in the best interest of Indigenous peoples to catch up with a superior, more advanced version of humanity, and to disappear into the new European, settler society. Colonisation was rosily envisaged by the new immigrant community of Australia as ‘the natural way of things’ and because of this attitude Indigenous culture was almost completely obliterated, not integrated, in the new settler society[iii].

After bearing the brunt of two hundred years of numerous assimilation policies, land theft, and economic marginalisation, the Indigenous cultures of Australia haven’t gone anywhere. There are a few reasons for this. Firstly, assimilation policies worked against integration and community wellbeing, because in practice they traumatised and marginalised people[iv]. Secondly, integration itself isn’t embraced when it is one-sided. Aboriginal persons were compelled to change everything and to fall in line with a European way of life, when the settler community changed nothing. Thirdly, when comparing the last two hundred years of Indigenous knowledge and testimony, alongside two hundred years of systemic racism, environmental degradation and human rights abuses displayed by the colonial enterprise, Western culture cannot claim the moral or cultural high ground.

Instead I would argue that the Indigenous cultures of Australia were and are on an alternative cultural trajectory. Western culture is a competitive, capitalist entity that champions progress and domination, whereas traditional Aboriginal cultures can be described as sophisticated environmental communities that place custodianship of the land as the central concern of cultural life. In the context of modern life, where Australians face bewildering economic forces, health and wellbeing challenges and climate change, the sustainable aspects of our ancient knowledges and cultures have become relevant once again. And now that Indigenous Australia is in recovery, supporting the return of traditional knowledges to the mainstream is not just about righting the wrongs of the past, but can contribute to the survival of all peoples in danger of obliteration or displacement in the new globalised world.

So, what next? After two hundred years of pushing back against colonial ideology and colonial practice, what is the next step? Can we start over, knowing what we know now? How do we de-colonise?

PRESENT-ING ART

Art can be a powerful medium for leadership in imagining what a decolonised Australia could entail. Quandamooka artist Megan Cope explores the reclaiming of geographical spaces in her Yunggulba – Flood Tide series exhibited at the Defying Empire exhibition at the National Gallery of Australia this year (pictured bottom)[v]. The exhibition featured thirty contemporary Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander artists and commemorated the 50th anniversary of the 1967 Referendum. Cope’s large scale works feature maps of familiar places such as Stradbroke Island reinstated with their traditional pre-colonisation names.

Cope makes an elegant challenge to European maps as the embodiment of the authenticity of knowledge, as she makes visible the erased Aboriginal custodianship of the Stradbroke Islands. She blends military maps with beautiful calligraphy of Aboriginal place and clan names to create a layered vision of that landscape. Cope’s approach to decolonisation is an act of remembering and acknowledgement, and envisions a future where we recognise the full history of a landscape, not just the history from 1788 onwards.

.aspx?width=450&height=222)

Decolonisation calls for supressed histories to be heard, which is a theme that runs through the works of Ryan Presley. Presley’s father’s family is Marri Ngarr, Aboriginal people who originate from the Moyle River region of the Northern Territory, and Blood Money is a series of paintings of Australian currency with the historical figures replaced with Aboriginal resistance fighters (pictured above). The series title suggests a critique of the understanding of wealth in Australia, namely how we come to be one of the top twenty wealthiest countries in the world.

In an interview on Awaye on ABC Radio National, Presley comments that ‘the blood of our people [has been] used to fuel this Australian economy, either through labour, or through mining and things like that. The Australian economy is very connected with Aboriginal people themselves, their own bodily entities, it has been built off Aboriginal backs’[vi].

The ten-dollar note has the image of poet Banjo Patterson replaced with Gurindji leader, Vincent Lingiari, who famously led the Wave Hill Walk-off, a protest movement that would lead to the Gurindji people regaining control over their ancestral lands. The re-envisaged banknotes imagine a world where the achievements of Aboriginal people are placed in high esteem in the new post-colonial Australia. The artworks also infer a nation that is ambivalent about the great economic benefit it has inherited through the historical practice of land theft.

Ghost Nets of the Ocean is a series of marine-themed sculptures that respond to growing concerns about the polluting of the world’s oceans. Erub (Darnley) Island is part of the Torres Strait, where a lot of debris from the fishing industry washes up. Abandoned fishing nets are a result of the over-fishing of our oceans and the haste in which fishing companies will pursue and stockpile fish, simply abandoning nets that get snagged or torn. The plastic net fish, squid, turtles and jellyfish of the installation are reminiscent of Head On (2006), Cai Guo-qiang’s gravity-defying animal sculpture. The work of the Erub Arts Collective is featured in the Art Gallery of South Australia as part of Tarnanthi Festival of Contemporary Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art at the Art Gallery of South Australia[vii].

The sardines of Tup (pictured left) are just a few of hundreds that were created by artist Lynnette Griffiths, who collaborated with not only the Indigenous community of Erub Island, but with the wider Facebook community, who sent in hundreds of their own ghost net sardines.

The sardines of Tup (pictured left) are just a few of hundreds that were created by artist Lynnette Griffiths, who collaborated with not only the Indigenous community of Erub Island, but with the wider Facebook community, who sent in hundreds of their own ghost net sardines.

This diverse project brought people from different worlds together to turn something dangerous and artificial back into something beautiful and organic.

The hanging sculptures could be simply read as environmental art, but I would argue that the marine forms also point to the capitalist ideology of Western culture to ‘produce, produce, produce’. Here different cultures came together on Erub Island to create art that celebrates their different cultural and personal connections with the ocean. It shows the compatibility of Indigenous ideas about land and sea custodianship with the growing global environmental movement. Tup suggests that it is collaboration, not division, that will help us face the challenges of environmental degradation.

THE FUTURE PRESENT

Decolonisation is ‘the unravelling of assumed certainties and the re-imagining and re-negotiating of common futures’[viii]. The ‘assumed certainty’ of Western superiority and Indigenous inferiority is a hangover from the past. To decolonise is to embrace that ‘common future’, to raise the voice of Indigenous experience and testimony through journalism, media, art, science, music, theatre and film. The artworks I have described represent ‘epistemological disruption’, that is, they challenge the status quo, and they disrupt the ‘assumed certainties’ of colonialism perpetuated in society long after colonialism was supposed to have ended. These artistic disturbances or disruptions are an essential part of decolonisation, of letting Indigenous history and knowledge have an equal place with European history. Decolonisation has no road map, no models from the past that we can emulate. It is two cultures starting a new conversation, much like meeting for the first time again, but from positions of equality.

The Australian art scene made space for Indigenous art initially due to its exoticness, scarcity and market value. Now is the time to understand the artworks, embrace their history, encourage a variety of Indigenous artists to share their creative testimonies.

It is time as artists to resist the images of Indigenous Australia portrayed in non-Indigenous media. Through acknowledging Indigenous history and testimony, Australia can shrink that ‘Great Silence’[ix] that eats away at our national identity, and have a future strengthened by the emerging renaissance of traditional knowledges.

Cassie Lynch is a descendent of the Noongar people whose ancestral lands comprise the south west and south coast of Western Australia. She is currently living in Perth and completing a PhD in postcolonial theory and Indigenous storytelling.

[i] Leela Gandhi says it best: Postcolonial theory is ‘a disciplinary project devoted to the academic task of revisiting, remembering, and crucially, interrogating the colonial past.’ Gandhi, Leela, ‘Postcolonial Theory: A Critical Introduction’, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1998, p. 4.

[ii] In The Doomed Race, Russell McGregor indicates that Indigenous Australians appeared particularly primitive to European colonisers due to their dark skin, lack of clothing, lack of recognisable government and inferior weaponry. They believed that, ‘following the law of evolution and survival of the fittest, the inferior races of mankind must give place to the highest type of man’. McGregor, Russell, ‘The Doomed Race: A Scientific Axiom of the Late Nineteenth Century’ Australian Journal of Politics & History, 39, 1993, p. 15.

[iii] Preeminent historian of the Stolen Generations in Western Australia, Professor Anna Haebich, states that ‘assimilation of Aboriginal people may be a comforting dream for Australians hankering after an imagined unproblematic past, but it is just that, a dream, and it has far outlived its relevance to our world.’ Haebich, Anna, ‘Imagining assimilation’ Australian Historical Studies, 33:118, 2002, p. 70.

[iv] One particular assimilation policy was the Aborigines Act 1905 (WA), where Aboriginal children were selected for an institutionalised childhood marked by abuse, neglect, servitude and loneliness based on the shade of their skin.

[v] Defying Empire: 3rd National Indigenous Art Triennial, 26 May to 10 September 2017, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra http://nga.gov.au/defyingempire/

[vi] Presley, Ryan. ‘The Colour of Money’, ABC Radio National, 8 June 2013, accessed 14 October 2017, http://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/awaye/the-colour-of-money3a-ryan-presley/4730184

[vii] Tarnanthi: Festival of Contemporary Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Art, 13 October 2017 to 28 January 2018, Art Gallery of South Australia and throughout Adelaide http://www.tarnanthi.com.au

[viii] Biermann, Soenke, ‘Knowledge, power and decolonization: implication for non-indigenous scholars, researchers and educators.’ In Indigenous philosophies and critical education: a reader, edited by George J Sefa Dei. Peter Lang, New York, 2011, p. 394.

[ix] Usually referred to as ‘The Great Australian Silence’, this saying refers to the selective amnesia of settler Australia, as “newly emergent postcolonial nation-states are often deluded and unsuccessful in their attempts to disown the burdens of their colonial inheritance.” Gandhi, Leela, ‘Postcolonial Theory: A Critical Introduction’, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1998, p. 4.

IMAGES

(top to bottom)

-

(detail) Ryan Presley, 10 Dollar Note – Vincent Lingiari Commemorative, Blood Money, 2011. Watercolour on arches paper, (96 x 45 cm), documented by Carl Warner. Licensed by Viscopy 2017.

-

Steaphan Paton, Cloaked Combat, 2013. Bark, carbon fibre, synthetic polymer resin and synthetic polymer paint, (l-r: a) 86.1 × 55.9 × 62.0 cm, b) 76.0 × 56.5 × 79.0 cm, c) 79.0 × 66.2 × 79.5 cm, d) 72.5 × 73.0 × 77.5 cm, e) 83.5 × 56.5 × 79.0 cm), installation view at National Gallery of Victoria (NGV). Licensed by Viscopy, 2017.

-

Megan Cope, Minjerriba, Mulumba, Moorgumpin Ngugi, Quandamooka, Yunggulba – Flood Tide series, 2014. Giclée military map and synthetic polymer paint on canvas, (each work 125 x 345 cm, overall 250 x 690cm), Installation view in Defying Empire: 3rd National Indigenous Art Triennial, National Gallery of Australia 2017, courtesy the artist and THIS IS NO FANTASY + dianne tanzer gallery.

-

Ryan Presley, 10 Dollar Note – Vincent Lingiari Commemorative, Blood Money, 2011. Watercolour on arches paper, (96 x 45 cm), documented by Carl Warner. Licensed by Viscopy 2017.

-

Lynette Griffiths in collaboration with Erub Arts and wider Facebook community, Tup, Ghost Nets of the Ocean, 2017. Reclaimed fishing net and rope, installation view at Tarnanthi Festival of Contemporary Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art, Photographer: Lynette Griffiths. Courtesy of the artist.