With MoMA gone, who's left holding the baby at AGWA?

With MoMA gone, who's left holding the baby at AGWA?

Victoria Laurie

So what happens now to the Art Gallery of Western Australia? All the precious eggs that went into a basket marked ‘MoMA’ have gone, and gallery director Stefano Carboni must now produce the goods in other ways.

The next few months may prove a greater test of Carboni’s curatorial and management skills than all the travails of MoMA’s three shows (and three aborted ones) put together. A big question looms over Perth’s state art gallery – which way forward?

By Carboni’s own admission, this question is being kicked around inside AGWA and among its board members. “We are debating internally who we are and where we want to go, who we want to be.”

Carboni and crew are grappling with thought bubbles that have popped to the surface, post-MoMA, in the minds of devoted gallery fans. Was the state art gallery effectively highjacked by the exclusive, tailormade shows from New York’s Museum of Modern Art? Has it lost time in building relationships with WA’s artists, including the Indigenous cultural renaissance on its doorstep?

On a broader front, is the gallery in danger of becoming alienated from its own public?

The MoMA series had some undeniable highs – including a respectable 230,000 visitors to three shows that gave Perthites exclusive access to masterpieces by Picasso, Warhol, van Gogh, Matisse and many others, and iconic images from 20th century New York photography.

The vibe surrounding these shows probably had the desired effect of luring newcomers inside the gallery for the first time. The series certainly attracted new levels of government support; nearly $12m in funding and other, in-kind backing from Eventscorp and WA Tourism for an ‘I ❤ New York in Perth’-style campaign.

But what now? Gaping holes created by three cancelled MoMA shows are being filled by shows like IMPACT, video art works purchased in the last few years. The works look handsome in the spaces purpose-built for Stranger than Fiction: Art of our Time, the fourth MoMA show. It was canned in December, a mere two weeks before nearly 70 fully documented, insured and crated works were due to be freighted out of New York bound for Perth. Newly opened is a Guy Grey-Smith show, a long-planned retrospective of the respected WA landscape artist; it will be followed by a Richard Avedon photography show, and then another ‘latest acquisitions’ show. If none of these events is wildly exciting, Carboni also hints that “advanced discussions” are in train for a solo exhibition of “a prominent living international artist from the northern hemisphere.”

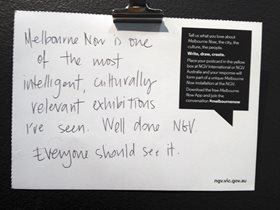

Watch this space. Meanwhile, the huge success of Melbourne Now, in which crowds flocked to see the work of living Victorian artists at the National Gallery of Victoria, has prompted an obvious idea about how to fill one of the MoMA voids.

“Melbourne Now has a sense that ‘this is yours – you’re here, be part of it’,” says University of Western Australia academic and curator Professor Ted Snell. “I would like to see a real focus on art practice in this part of the world because you won’t see it anywhere else."

“Melbourne Now has a sense that ‘this is yours – you’re here, be part of it’,” says University of Western Australia academic and curator Professor Ted Snell. “I would like to see a real focus on art practice in this part of the world because you won’t see it anywhere else."

"The only place you’ll see what’s going on in Perth is Perth. But you don’t see much evidence of it if you go to the state gallery.”

Helen Carroll, a board member of AGWA and curator of Wesfarmers’ art collection, clearly believes there is merit in Snell’s argument. While she stands by the state gallery’s MoMA-linked bid to be “ambitious and daring with programming”, she says AGWA should also be “celebrating the local and regionally specific.”

“The voice of our own artists coming back strongly into our institutions – that needs to happen more," she says. “We should be celebrating exhibitions that are fully about our culture, (as) a living, breathing institution that the community thinks reflects itself.”

Carroll favours gallery-artist partnerships in which “artists have space to push themselves and there are opportunities for curators to work with our living artists... These relationships need to be fostered and we haven’t been doing that as much as we could.”

“We also have an incredible tradition of living, breathing diversity of Indigenous culture. It’s something we can own and have civic pride in.”

Carroll’s views, which presumably she is pushing at board level, go to the heart of another criticism of AGWA’s current public profile. What traits does it have that differentiate it from other state galleries?

Several interviewees for this article nominated Queensland’s Gallery of Modern Art as having carved out a unique niche. Says Snell: “They established the Asia Pacific Triennial and cleverly bought from it – partly to save money on freight to send works back! They now have a collection that is second to none in the world.”

“But we have distinctive, unique aspects too,” he adds. “We’re right on the Indian Ocean so we’re connected to a set of cultural and political exchanges. We’re in the same time zone as 60% of the world’s population. And we have one of the richest and oldest cultures sitting right here that is not acknowledged as it should be.”

AGWA has made commendable efforts in hosting the annual Indigenous Art Awards (Australia’s richest Indigenous art prize, although it remains vulnerable to Barnett government budget cuts). And the gallery has launched a five-year project called ‘Desert, Land, Sea’ with the Kimberley community, which may well bear rich fruit down the track.

But AGWA could be eclipsed if it is not careful. The University of Western Australia is planning its own Indigenous art centre to house its substantial Berndt Collection of art and objects. There are on-again off-again plans for a major Indigenous cultural centre for Perth; there are even bigger – but vaguer – plans for a national centre of Indigenous culture somewhere in a capital city. If any one of these actually materialises, it could rob AGWA of its status as a ‘go-to’ repository of Indigenous art in WA.

Carboni has stated his hope that the AGWA-MoMA partnership would prise open the doors of prestigious overseas galleries to Western Australian art; if we show interest in them, they might show reciprocal interest in our cultural output. Yet here again, AGWA risks losing the relevance game.

Via cyberspace, local artists are already leapfrogging their way into the international spotlight. A case in point is Perth-based SymbioticA, a cutting-edge science-art collective with a global following; it has not yet had its own show at the state art gallery. Says Snell: “It’s a good example because SymbioticA shows around the world, in Beijing, Berlin and New York – even at MoMA! Yet we don’t showcase them in Perth.”

Carboni concedes this point. “It’s very true, this is an internal debate that we are having and I’ve had several discussions with [SymbioticA’s] Oron Catts. I’m sure it will happen at some point.”

That Carboni seems to lack a slight sense of urgency may be related to his conviction that Western Australian art is not AGWA’s primary target. Nor does he favour the kind of single-minded focus that Melbourne Now represents at the NGV.

“We regularly do shows that deal with contemporary artists in WA,” he says, “and I don’t particularly like to copy ideas. I’m very much of the idea that contemporary art is a global phenomenon, and I don’t necessarily want to limit it to the specificity of WA artists.”

“From my point of view, we are supporting (them) to a great degree because 45-50% of acquisitions are of WA artists,” he says. The actual figure in 2012-13 was 38%.

He continues: “We receive endless complaints and letters from a range of WA artists that say ‘oh you bought a work of mine in the 90s and then you never collected me any more’. I have no problems in being very, very open and direct with them. I say ‘well, in our opinion you haven’t done enough in the past few years for us to consider acquisitions.’

“We are the state art collection so we don’t necessarily have to have a single focus on the art that is produced in WA. It doesn’t happen in Queensland or New South Wales.”

Tony Jones, one of the state’s high profile sculptors, is among those artists who has sent letters and even made personal representations to gallery executives, in a plea for greater “dialogue and advocacy”. He sat on AGWA’s board for eight years in the 1980s and 90s, under two former directors.

“I saw a happy bunch of artists and a good rapport with the gallery. I would argue that embracing a constituency is not about buying their work but about inviting them to openings, visiting exhibitions to see artists work, being in dialogue.”

He says the gallery does not seem to “have a deep and abiding interest in WA culture, and it has alienated many among a generation of artists. Yet they are the gatekeepers of our culture.”

On this point, Carboni might like to review his own gallery’s acquisition policy which “… aspires to develop the finest public art collection of Western Australian art in the State.” It goes on: “The priority is to develop a comprehensive collection of Western Australian art and design.”

And AGWA’s boss might note the views of Morris Hargreaves McIntyre, the UK consultants it hires to provide it with marketing advice. On its website, MHM describes the state gallery thus: “One of the Collection’s key strengths is its pre-eminent holdings of Western Australian indigenous and non-indigenous art.”

It’s unclear whether AGWA’s board will demand more oversight and greater input into gallery affairs after the MoMA disappointment. For her part,

board member Carroll supports the idea of offering “significant commissions” to local senior artists, preferably in partnership with Perth’s major private collections – like the Kerry Stokes, Holmes á Court and Lepley collections. “It would extend their practice and create national impact. To me that feels like the next wave.”

Carboni says Perth’s private sector is being invited to invest in the gallery’s future. “I can assure you that a lot of discussions are taking place, and there will be some results soon.”

Meanwhile, he is philosophical about the end of the MoMA dream. “We have to move on, accept that this was an incident in a long journey and take it as positively as possible. This is an opportunity to think more closely about who we are and think more strategically about our future.”

Many in Perth will be hoping that from this introspection emerges a state gallery with a new sense of purpose.

Victoria Laurie is a Perth-based arts writer and reviewer for The Australian and ABC online.

This article featured in the Artsource Newsletter, Autumn 2014.